Building a Hindley Milner Type Inference System for Airscript

The original company blog link no longer exists after Airkit was acquired

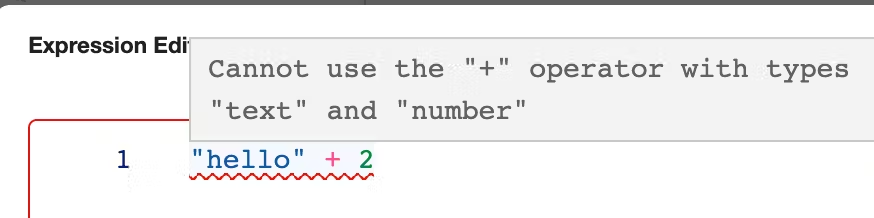

At Airkit, we developed our own programming language called Airscript. When developers build apps with Airscript, we want them to feel confident about the code they write. This is the job of Airscript’s type checker. It helps developers catch errors before they even run their code.

The figure below showcases Airscript’s type checker warning developers that they cannot add text with a number.

Type checking doesn’t come without a cost. Some programming languages require developers to provide type annotations for expressions to enable type checking. This may be cumbersome for developers and sometimes makes the code less readable.

Type inference solves this problem. Type inference is a technique for a compiler to automatically infer the types of expressions without the need for type annotations. Languages that support type inference include Typescript, Rust, Haskell, etc.

One of Airscript’s core design principles is simplicity. Type inference aligns with this design goal as it enables developers to omit type annotations. In this blog, I will talk about how I built a type inference system for Airscript using Hindley Milner’s type inference algorithm.

What is type inference?

Looking at some examples is the best way to understand what type inference is.

In the expression below, what can we infer about the type of a?

a + 2;

It has to be a number. This is because + takes two numbers as operands.

Let’s try a harder example. What can we deduce about the type of a?

a[0] + 2;

It has to be a list of numbers. By the + operator, we can deduce that a[0] is a number. By a[0], we can deduce that a is a list of numbers.

We just performed type inference! As we can see, type inference is the process of deducing the type of expression based on its usage.

Type Checking with Type Inference

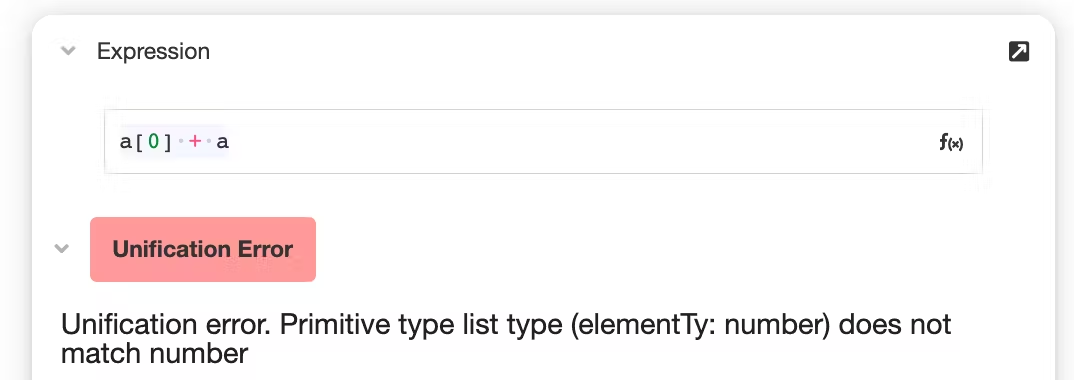

Type inference can be used to catch type errors that are otherwise hard to catch.

In the example above, let’s suppose we have a variable a with an unknown type. The type checker is able to use type inference to catch a type error - a cannot be both an array of numbers and a number.

Here are the rough steps the type checker took to catch the error:

- By

+, the type checker knows that botha[0]andaare both numbers - By

a[0], the type checker knows that a must be a list of number - Step 1 and step 2 contradict each other -

acannot be both a list and a number.

The example below is similar to the one we just saw. The type checker is able to recurse into the object and realize that the inferred type based on a[0] and a+1 contradict one another.

As we can see from these examples, the type checker uses type inference to generate a set of statements about the variables. It then sees if the statements contradict one another to decide if there is a type error.

Hindley Milner Type System

Almost every statically typed functional programming language, such as Haskell and OCaml, that has type inference is based on the Hindley-Milner (HM) type system. The HM type system comes with a type inference algorithm called Algorithm W which is the basis for my implementation.

The idea behind the algorithm is similar to something we’ve all done before in middle school - solving a system of equations.

Let’s assume we have the following equations:

y = 2

x + y = 5

What we mean by “solving” this system of equations is to come up with a set of substitutions from variables to numbers that satisfy all the equations. In this example, the substitution [y=2, x=3] is valid because it satisfies both statements.

Some systems of equations may be invalid. In the example below, we cannot find a valid substitution for x because x cannot be both 3 and 2 at the same time.

x = 3

x + 1 = 3

In constraint satisfaction problems, we refer to this contradiction as a unification error, because we are unable to unify the statements.

The way the HM algorithm infers types is very similar to how we solve a system of equations. Instead of trying to find substitutions from variables to numbers, we try to find substitutions from variables to types. Let’s look at Hindley Milner’s algorithm in more detail.

Type Inference Algorithm

The core idea behind Hindley Milner is that every expression has a type. Each type is given a type variable. The algorithm will walk the expression tree recursively and collect constraints about the type variables. Type inference is the process of collecting and solving these type constraints. If the constraints conflict with one another, we have a type error.

As the HM algorithm walks the expression, it maintains a type environment stack, which stores the variables accessible by the current expression. Type environments are similar to symbol tables that compilers use to store scoped variables.

Let’s try and infer the type of the following function

def f(a) {

a[0] + 2

}

Here are the steps of the algorithm:

- First, we assign type variables to the function’s input and output, which are

T1andT2respectively. Therefore, the function f has typeT1 → T2. - Next, we extend the type environment to

[a: T1]and recur into the body of the function -

- We look up the type scheme of +, which is

ForAll[] (Int, Int -> Int). The empty list next to ForAll means that + does not have generic type parameters. -

- The first argument is a[0]. This is an indexed binding. The scheme of indexed binding is

Forall ['X], (['X] → 'X). This means that indexed binding takes alist of 'Xand returns'X. We instantiate the type to give['T3] -> 'T3. - We know that a‘s type variable is

T1. So we unify['T3] -> 'T3withT1 -> Intto obtain the substitution[T1 = [T3], T3 = Int]. We then simplify the substitution to get[T1 = [Int], T3 = Int]. The type ofa[0]is an Int.

- The first argument is a[0]. This is an indexed binding. The scheme of indexed binding is

- The second parameter is an Int, so no more work must be done.

- We look up the type scheme of +, which is

- We unify the return type of + with

T2, the type variable for the output offto get the substitution[T2 = Int]. - Finally, we apply the substitutions we have collected so far

[T1 = [Int], T2 = Int ]toT1 -> T2to conclude thatf‘s type is[Int] → Int.

Let’s look at more examples!

Variables and Type Variables

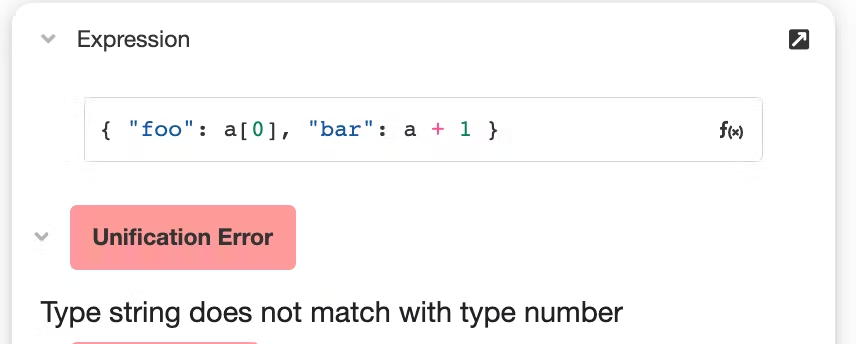

To make debugging the type inference algorithm easier, I built a visualizer tool to list out all variables and type variables.

In the image below, I took screenshots of the variables and type variables for 3 different expressions with the same scope.

In frame 1, we can’t infer much about the variable, so a ‘s type is still the type variable.

In frame 2, we can infer that a is a list type. However, we don’t know the type of list. Therefore, the type of a is a list of T39. We can also see from the type variables that T37‘s substitution is a list of T39.

In frame 3, by + 2, we can infer that T39 is a number. Therefore, a ‘s type is [number].

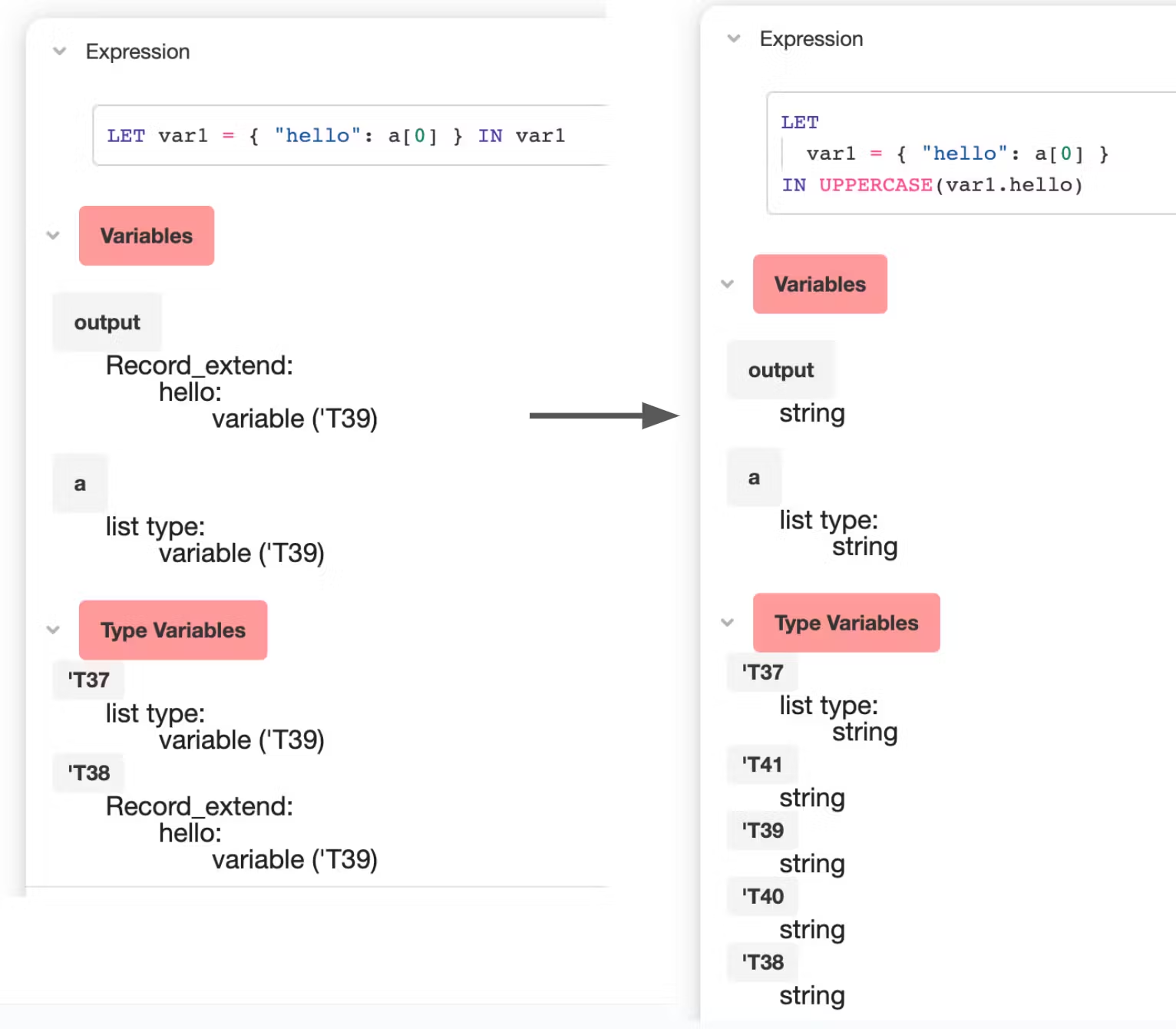

Let-In expressions

Some expressions can create new scopes and scoped variables. Let’s look at how HM deals with the Let-In expressions.

Let-In expressions create temporary scoped variables that are only available in its body. In this example, we declare a variable var1 and initialize it as an object. In frame 1, the output of the body has a type of { hello: T39 }, where T39 is the element type of a.

In frame 2, we can deduce, based on the UPPERCASE(var1.hello) that var1.hello is a string. Therefore, T39 is a string. We can also infer that a is a list of strings.

We can see in this example that variables and type variables form an interconnected graph. Adding a new constraint into the graph may cause rippling effects to allow the system to infer seemingly unconnected nodes.

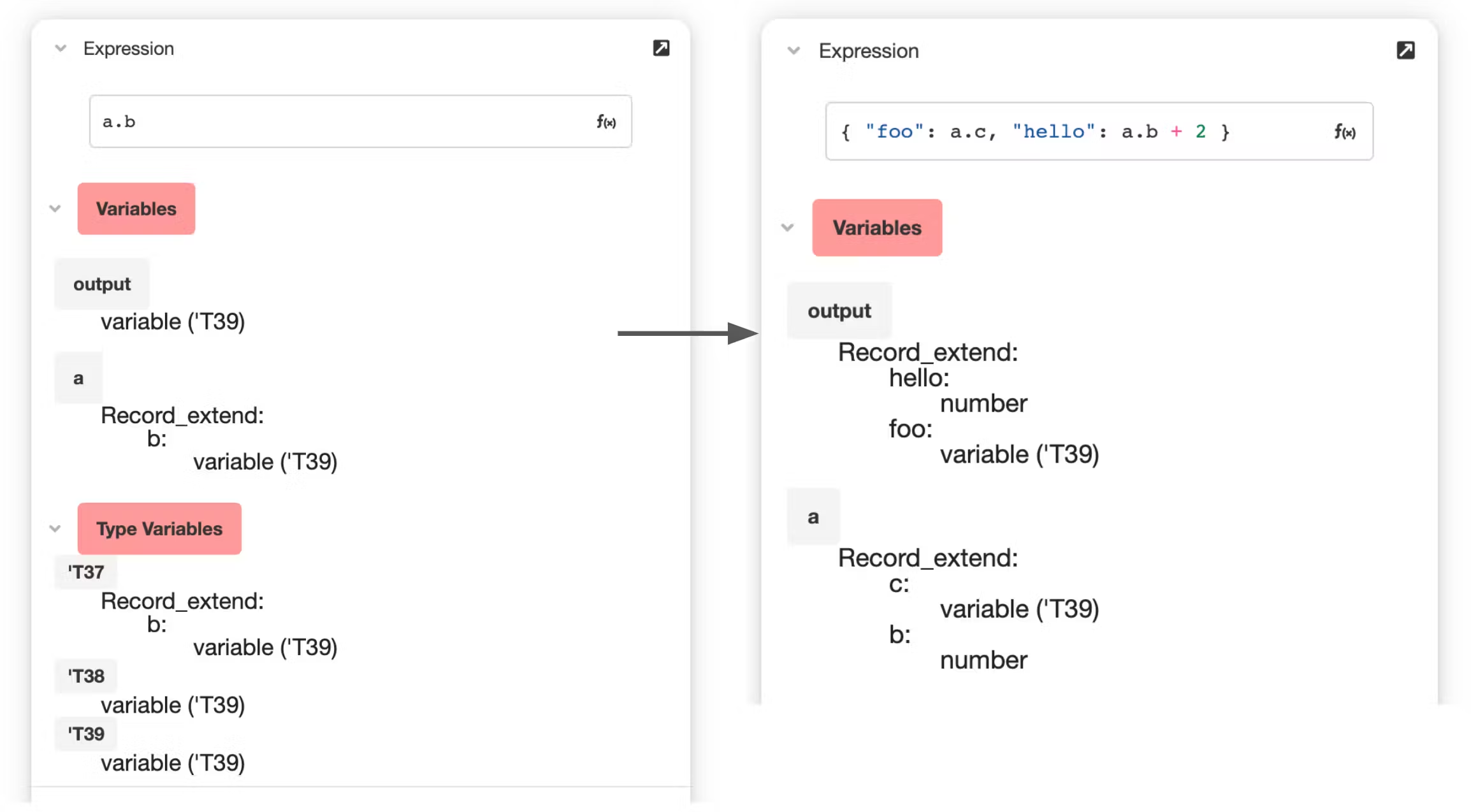

Row Polymorphism

The HM type system doesn’t have first-class support for the record type. Luckily, there is an extension to HM called row polymorphism that supports the record type.

The core idea behind row polymorphism is that records can be extended into bigger records. A record type in this type system can be written as { t1: T1, … tk: Tk, ρ}. The rho (ρ) is a polymorphic variable that represents a variable that can be instantiated to extra fields.

Let’s suppose we start with a record variable a. Its type is { ρ }. If the compiler encounters a.b + 1, it extends the type of a to { b: number, ρ}. In other words, each record type has the power to keep extending itself.

In this example, the variable a extends from a record containing just b to a record containing b and c.

Conclusion

Building a robust type system for Airscript is a never-ending journey. Luckily, there are a lot of research and programming languages we can draw inspiration from. This is the type of work I enjoy the most - bridging the theoretical world with the real world. I love finding ways to incorporate cool concepts like Hindley Milner into our product to help our developers solve real-world problems in industries like finance, insurance, e-commerce, etc.