Life of A Query

Now that we understand how CRDB guarantees atomicity and isolation for its transactions, we can finally start implementing the transactional layer!

The transactional layer of the toy database is composed of many entities. This page serves as a high-level overview of how a query interacts with these entities. You don't need to fully understand this page as I will cover each entity in greater detail. But hopefully, this page serves as a useful reference for understanding how each entity fits into the life of a query.

This page is inspired by CRDB's Life of a SQL Query doc, which outlines the lifecycle of a single query through the different layers of CRDB. I found that doc extremely useful when learning how CRDB works.

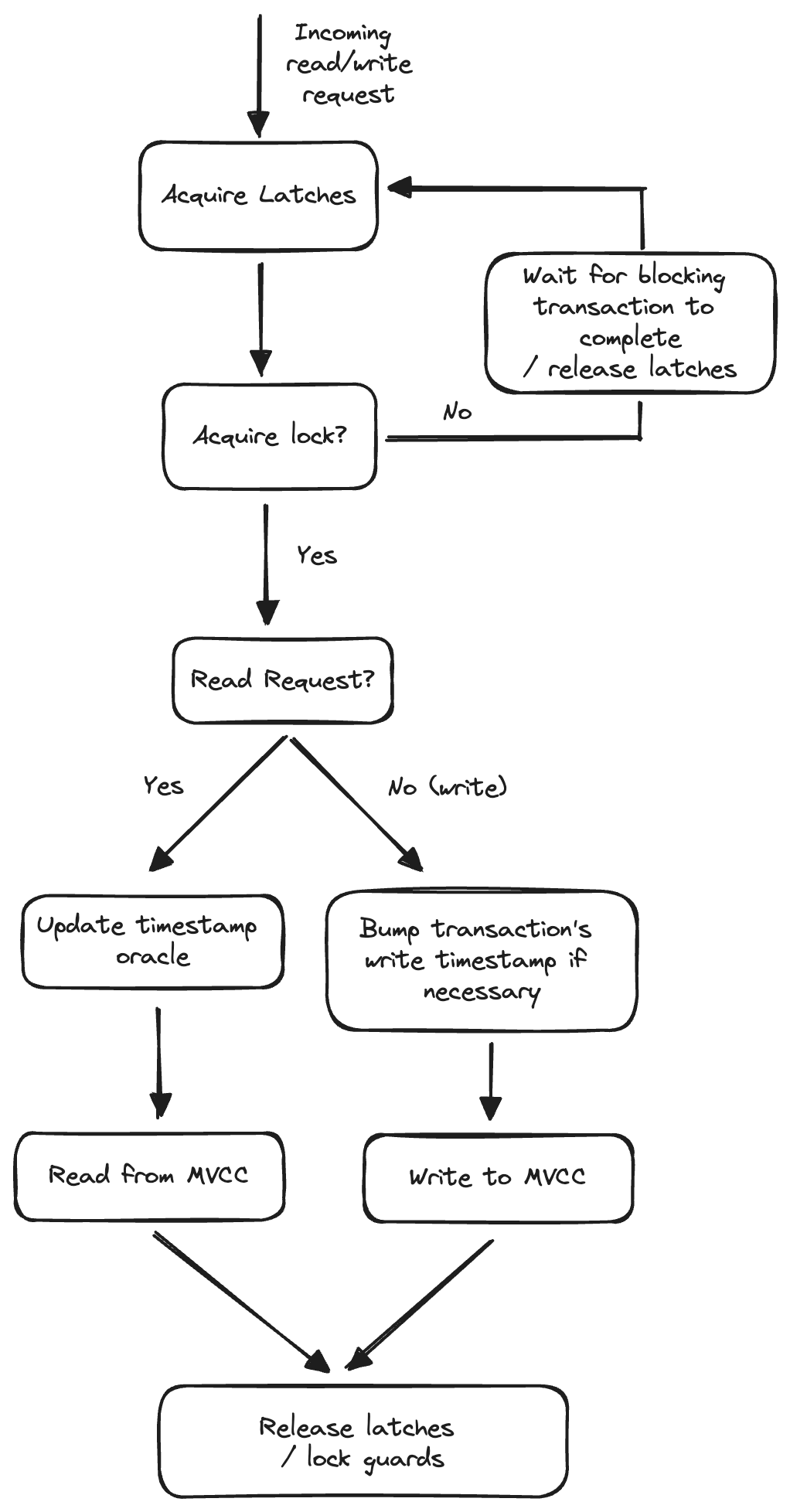

Here is a diagram showing the higher level life cycle of a read/write request:

The transactional layer of my toy database is composed of these entities:

- Concurrency Manager: Provides isolation to concurrent and conflicting requests by sequencing them. Once a request is sequenced, it is free to execute as no conflicting requests are running at the same time. The concurrency manager is made up of the latch manager, lock table, and transaction wait queue.

- Latch Manager: Serializes accesses for keys. Only one latch guard can be acquired for a key at any given time.

- Lock Table: Hold locks. Each lock corresponds to an uncommitted write by a transaction. Each lock may have a queue of waiting writes and a queue of waiting reads. The lock outlives the request since a transaction is composed of multiple requests.

- Transaction Wait Queue: Stores the pending transactions for each transaction. This queue is responsible for detecting transaction deadlocks when there is a cycle in the “waits-for” graph

- Executor: Executes the request. This involves reading and writing to the MVCC database built on top of RocksDB

- Hybrid Logical Clock: Generates unique, incrementing timestamps that have a wall clock component and a logical component

A Request is a unit of execution in the database. Types of requests include start/abort/commit transaction, read, write, etc. The entry point of a request is execute_request_with_concurrency_retries, which involves a retry loop that attempts to acquire latches/locks and executes the request. If the request runs into write intents, the method handles the write intent and retries.

Acquiring latches and locks

Because the database is thread-safe, the database can receive multiple concurrent requests. ConcurrencyManager::Sequence_req is called to acquire latches and locks so that the request has full isolation.

Sequence_req first figures out what latches and locks to acquire by calling collect_spans. Each request implements a collect_spans method that returns the latch/lock keys the request needs to acquire. For example, a WRITE("A)'s collected keys would be: ["A"].

Next, the manager acquires the latches. If the latch is held by another request, the manager needs to wait until the latch is released because each latch can only be acquired by one request at any time.

The manager then tries to acquire locks. If the lock is taken by another transaction, the manager needs to wait for the conflicting transaction to finish (or attempt to push the transaction). While it waits, the request needs to release its acquired latches. This is because latches need to be short-lived.

The manager keeps looping until all the locks have been acquired. Each time it loops, it reacquires the latches.

Once the latch and lock guards are acquired, the executor is ready to execute. At this point, the request has full isolation. Executing read-only requests is slightly different from executing write requests.

Executing read-only requests

As covered in an earlier page, the database tracks the latest read timestamp performed for every key. This way, when a transaction tries to perform a conflicting write, its write timestamp is advanced to the timestamp after the latest read timestamp.

The database uses the timestamp oracle to track all the reads. Therefore, the executor updates the oracle after performing the read.

Executing write requests

Before performing writes, the request may need to bump its write timestamp to prevent read-write or write-write conflict. Therefore, it fetches the latest read timestamp for each key it needs to write from the timestamp oracle. It then advances the transaction’s write_timestamp if necessary. After advancing the write timestamp, it can execute the request.

Performing the Request

Each request implements the execute method which interacts with the storage layer. The storage layer of the database is built on top of RocksDB. As an example, the PutRequest’s execute implementation puts the MVCC key-value record into the storage layer. We will cover the execute method for each request type in more detail later.

Finally, the executor finishes the request - releasing the latch guards and dequeuing the lock guards.

Now, let's look at the implementation details for the entities that make up the transactional layer!